The "year with bell hooks" Project: Letter #002

All About Love: Justice - Childhood Love Lessons

Hi, all, and a special welcome to our new readers since the last letter! Chapter 2 has so much insight packed in these 13 pages; let’s get into it, shall we?

To my child’s mind, love was the good feeling you got when family treated you like you mattered and you treated them like they mattered. Love was always and only about good feelings. In early adolescence, when we were whipped and told that these punishments were “for our own good” or “I’m doing this because I love you”, my siblings and I were confused. Why was harsh punishment a gesture of love?

All About Love - p.17

The Vulnerability of the Child/Inner-Child

When reading this chapter, one of the ongoing questions I had was, “what does it mean for something to become normalized? And who or what makes it true?”

Mainly because this chapter focuses on childhood, I began to think about the things my family/community would coin as normal and necessary, which just left little room to inquire about whether those things were true or not. So when hooks transitioned this chapter to focus on childhood punishment as the antithesis to love, I knew then that these words might hit a little too close to home.

There are many verses in the Bible that I wish could just un-exist. Proverbs 13:24 (“Whoever spares the rod hates his son, but he who loves him is diligent to discipline him.”) or where we get the phrase - spare the rod, spoil the child, absolutely takes the cake.

And one of the reasons why I wish that verse, among many others, could disappear is in the way it’s been misinterpreted, ill-applied, and intentionally used to exploit and harm the most vulnerable.

So, what does it mean for children to grow up in a culture where punishment (spanking, beating, yelling, etc.) is normalized and encouraged? What does it mean to be a child in a place where repetition becomes truth, where what is normalized becomes law, where what is law becomes religion, and this religion is our law (gathered from Critical Race Theory Lecturer Attorney Cooks)?

We have to see that what appears as sacred, righteous, necessary, or sanctioned in our society today (I’m referring to the normalizing of child punishment - physically, emotionally, verbally, or mentally) are only just false guises to allow and give room for abuse, neglect, and harm to occur. If we don’t, our inability to interrogate what seems, what appears, or what “is” normal only gives validity and an audience to the very things that are death-dealing. That is the evil, not “unruly” kids.

Vulnerability is a growing word that many circles use more frequently. But I’m also suspicious of that word. What does maintaining vulnerability as a child mean? To whom do we remain vulnerable? And, is there a shared understanding and vocalized commitment to trust and safety in that relationship to maintain vulnerability? Because if not, vulnerability is a wonderful tool to keep exploitative power dynamics in place.

I say this as I reflect on conversations that address the importance of nurturing your inner child. And I think that is soooo soooo important. Healing and transformation leaps from this focus. But what does addressing your inner-child look like in noting the difference between material self-love and self-love that’s not solely grounded in the material? What does addressing the inner-child look like in a capitalistic structure that thrives on our vulnerabilities? And once it’s clear that America is America only because of its roots in its theft of both land and bodies (gathered from Critical Race Theory Lecturer Attorney Cooks), hooks’ interrogation of our normalization of punishment should waken us up to the ties that still bind us. There is nothing freeing, growth-nurturing or loving about abuse and punishment. Nothing. I stand ten toes on this.

Yea, We Have to Talk About the F-Word

Forgiveness (sorry y’all, I’m not ready to cuss on here yet!) is also another word I’d strongly consider getting rid of too. Simply because it’s also been misused and harmfully applied.

In all of chapter 2, there was like a mini-ticker going off in my mind of “surely everything wasn’t bad of your childhood,” and though yes, the mini-ticker was true, I think there is a time and place for “positivity” to shine through that doesn’t put a blinder on addressing what is not ok.

“Your parents did the best they can” or “your parents are humans too” are all true statements and ones that I believe. Still, if those statements are shared to silence a necessary interrogation on why things happened the way they did (childhood speaking), then those statements are especially concerning.

Forgiveness, like love, both need clear and necessary definitions for us to properly apply individually and communally. They are beautiful and healing in their unique and often intertwined ways.

But, to ask the harmed to forgive when the harm-doer hasn’t even acknowledged their harm? WILD.

Like last week’s question, is it love, or is it cathexis? Is it forgiveness, or is it absolvement?

Because, if I were to look at forgiveness in the context of my family dynamic, forgiveness - in essence, is the immediate expectation to “forgive” the harm-doer as a way to preserve and protect the collective image of the family - not rectify the wrong.

Look, if there’s anything about this personal and social transformation journey, it’s about not giving two shits (I guess I spoke too soon) about preserving what is harmful - simply because it is just that…harmful!

We, as people raised in families/communities/societies adopting harmful, toxic, and oppressive ideologies about life on earth and the life to come, have the tendency to forgo interrogating those who have caused harm and/or hold more power than ourselves by believing that peace looks like the absence of conflict in order to ironically not trouble the already troubled waters.

So, we must ask ourselves, “what must be done”?

I believe that we don’t have to look as far as we think. We must look at our stories. We must begin to inquire about the how and why we are and the how and why we’re here. We have a right to know our origin, we have a right to know our history, and we especially have the right to question incessantly why those in our social/religious context do what they do.

It Gets Gory Before it Gets Good

In building our/the new body, the re-membering of hooks’ definition of love is essential for transformation.

While we understand love as

An act of will - namely, both an intention and an action. The working definition for love is partly from Erich Fromm (The Road Less Traveled), where love is “the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth … love is as love does. Will also implies choice. We do not have to love. We choose to love.” “To truly love, we must learn to mix various ingredients - care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication

All About Love - pgs. 4-5

Hooks reminds us that

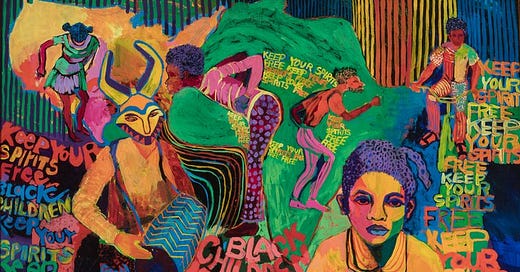

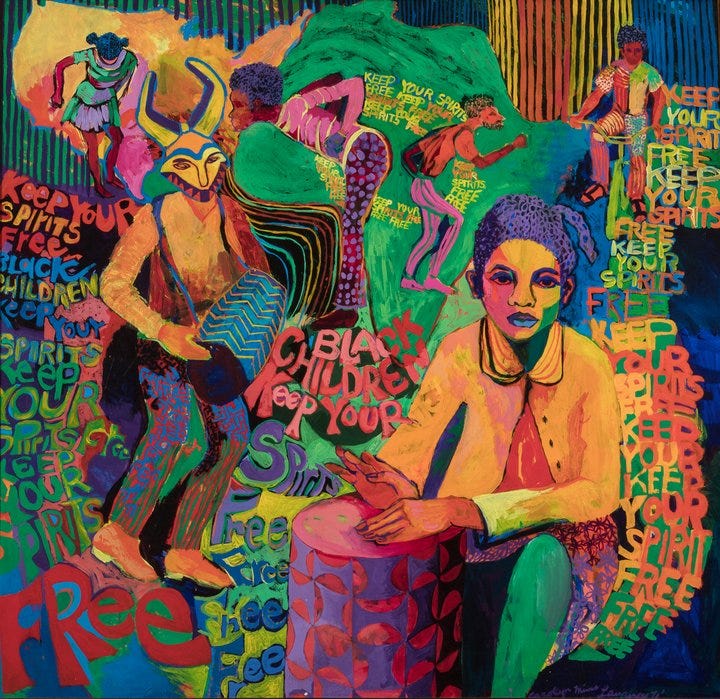

Love is as love does, and it is our responsibility to give children love. When we love children we acknowledge by our every action that they are not property, that they have rights—that we respect and uphold their rights.

Without justice, there can be no love

All About Love - pg. 30

Until next week and with love,